Crucial to understanding how far things can go in Bruegel’s and Ensor’s (etc) work is to see that they were able to paint or draw different, overlapping portraits in the same spot. Which at the same time offers us an explaination why they often use kind of “surrealist” surroundings and weird and/or strangely positioned creatures: it enabled them to take things further when it comes to this type of visual trickery.

So I’m not talking of anamorphosis now, but about portraits hidden in plain view.

Before giving an example of how Bruegel worked, the following: visual trickery was often used, and mostly by artists who were of course far less brilliant than Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Dürer or Leonardo. But this means that the work of these is far more accessible, and that this gives us an opportunity to learn.

E.g. In the work of Bruegel and followers you often see birds or strange creatures in the skies. In the following engraving by Jan Collaert, it’s quite easy to see why: because it’s part of a hidden portrait.

But of course things probably go further:

Now: can we be sure the artists meant the example above to be seen this way? Well: no we can’t. But as I said before: it’s the clearest examples that make the case. In combination with the numbers of course: when you notice something is going on once – as I’m sure we all have – you’ll think “Ha, that’s a bit of fun there”. When you notice this ten times you’ll think “Hey, that’s weird”. When you notice this a hundred times, you’ll think “Wait a minute, what’s going on here?!”. And when you’ve seen hundreds and hundreds (thousands?) of clear and less clear weird things going on, you’ll know the less clear ones aren’t all that important. What is important is that there’s enough clear examples that indicate that something’s going on: it’s how some of these Renaissance-artists worked.

So, Bruegel. Take a look at the overlapping faces in the following drawing. The first one a woman’s face, profile to the right (black my marking)

So you end up with an extremely complex cluster of rotated, overlapping faces.

An example of Jan Bruegel: some of the (potential) hidden faces marked

?

?

Apart from Jan Bruegel, there’s other painters of the StLuke guild that have painted forests that can be completely deconstructed into faces. (The same with rocks, skies, crowds, rooftops,… ) Incidentally, I went for a walk in the forest 2 hours ago. Number of faces I was able to spot there: 0. Number of faces I can spot in works of artists who don’t deliberately hide these: 0.

I spoke of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Procession to Calvary earlier, with the potential portraits of Leonardo and Erasmus in it. On a bigger scale, there are potentially some hard to see portraits in there:

In case it would seem arbitrary where I put these markings: I actually merely highlight existing colour- and lightboundaries within the paintings.

The Procession to Calvary rotated, a potential portrait comparable to the marked figure hidden on the left in The Tower of Babel below…

It seems similar portraits now and again pop up on a large scale. Depicting Phillip II of Spain (with the Habsburg Jaw) and Margaret of Parma?

Another thing I know by now: the use of visual trickery was widespread in Italy in the Renaissance period as well. Makes one wonder what information can be unveiled this way in due time.

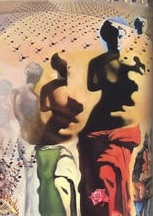

And of course there’s 20th century artists you can compare this all with (detail of a painting by Salvador Dali, photo sent to me by Tom Jacobson. Thanks Tom!):